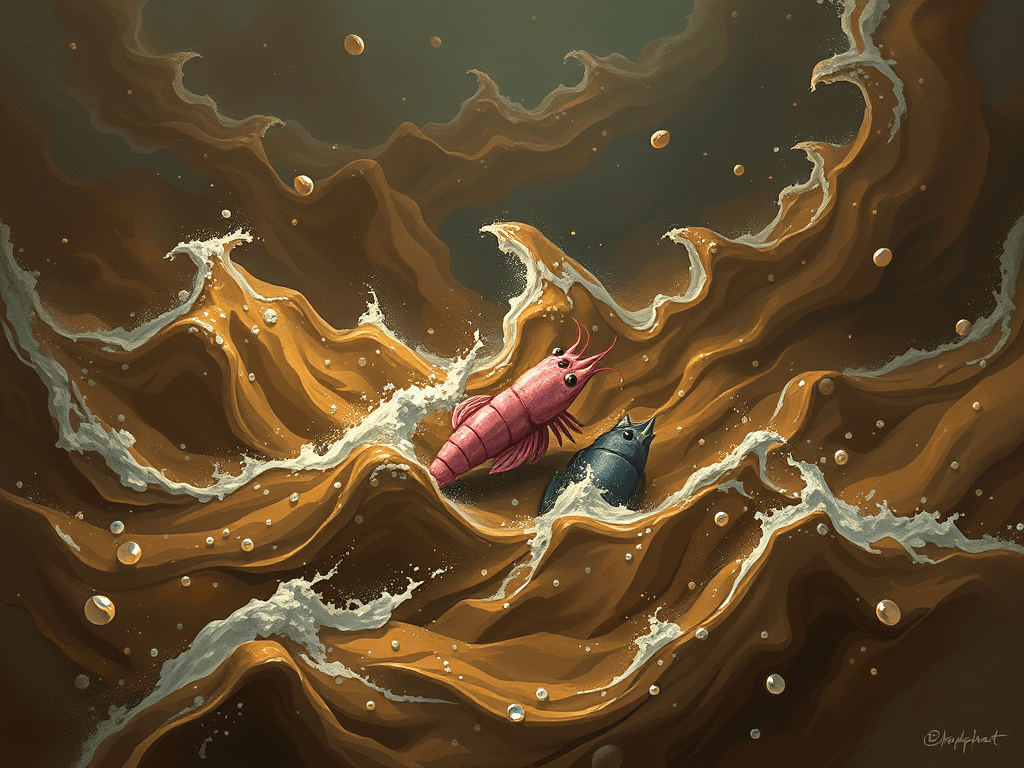

I recently attended an online symposium held by Anglia Ruskin University on brain rot, AI slop, and the enshittification of the internet. The experience was clarifying in ways I hadn’t anticipated (as well as a lot of fun, I have never before seen so many terrible memes in one placee!) For a while now I’ve been thinking of one of the big challenges that AI represents as the “Sea of Sludge” – my term for the flood of algorithmically generated, homogenised content drowning the online world. The symposium helped me tease out the difference between sludge and slop, and understand why the distinction matters.

To me the Sea of Sludge describes something broad and almost inevitable: the proliferation of generic AI-generated prose that is grammatically correct but devoid of passion, originality, or distinctive voice. It’s what happens when text production becomes trivial. Most future published text will likely be AI-generated, and if we are not careful it will be technically fluent but trending toward the statistical middle, flattening out the vibrancy of human expression.

AI Slop is more specific and in some ways more troubling. It’s intentional. Slop isn’t just generic content appearing as a side effect of automation, it’s low-quality material deliberately produced to game attention economies. Its spam culture evolved, leveraging AI to increase scale whilst maintaining the same underlying logic: capture attention through volume, ignore value creation entirely. There are communities of “sloppers” mass-producing content not because they have something to say but because platforms reward engagement metrics over substance.

At the individual level, this behaviour connects to what Maria Gemma Brown described as “hustle culture”, the fantasy of passive income through platform gaming, driven by financial precarity rather than simple greed. The infinite money glitch framing reveals the underlying belief: the system is broken, so exploit it. But the phenomenon operates at scales beyond individual hustlers.

Xichen Liu made the same point, but with a big picture lens, applying Georges Bataille’s concept of the accursed share to data capitalism, reframing AI slop not as market failure but as inevitable surplus. Bataille argued that economies are fundamentally about what to do with excess rather than how to allocate scarce resources. Productive systems always generate more than can be reinvested. This surplus, the accursed share, must be expended somehow, either luxuriously through art and celebration, or catastrophically through destruction.

Applied to computational capitalism, this is powerful perspective change. Excessive data production, bot content, AI slop, these aren’t anomalies. The slop is capitalism’s accursed share of computational capacity and content, surplus that must be produced and expelled. The Dead Internet Theory (the endpoint of enshittification where the web is drowning in bot noise) becomes comprehensible as the catastrophic expenditure of our computational excess.

We’ve built systems capable of generating effectively infinite text. So what did we expect would happen? The romantic hope was that AI assisted humans to produce better, richer content. The reality at present is closer to Bataille’s vision: we’re expending the surplus through floods of meaningless material because the system must vent. The sewer demands an outfall pipe.

This connects to why slop feels different from earlier content pollution (from email spam or SEO farms, for example). AI slop occupies an uncanny valley: good enough to pass initial filters, poor enough to feel hollow, and produced at such scale that it threatens to become the baseline. It’s not just that there’s more content. It’s that the economic logic has shifted from value creation to surplus expenditure. Unlike its predecessors it is a feature of the system, not a bug.

The consumption side is equally interesting. AI slop has its own aesthetic, an emerging digital culture that has a purpose. Brain rot (the term for mental deterioration from overconsuming deliberately meaningless content) was described at the symposium as “pleasant numbness.” It’s experienced as relief rather than harm, a comforting anaesthetic against everyday stresses. Where doomscrolling involves compulsive consumption of overwhelming meaningful content driven by threats, brain rot involves consuming content optimised to eliminate thought entirely. Both are pathologies of attention, but brain rot is the one that feels good. It is our Internet Soma.

Alan Warburton, director of “The Wizard of AI”. posed a provocative challenge at the conclusion of his talk: might AI slop function as a rhetorical obstacle, allowing scholars to avoid direct engagement with industrial image technologies? Framing the generative AI industry as low-quality nonsense may be strategically convenient, dismissing slop as beneath serious analysis even as the industrial systems producing it grow into monstrous scale, potentially cutting off critical access to their workings. This raises uncomfortable questions about whether slop discourse serves defensive purposes, creating distance from systems that demand closer scrutiny precisely because they’re becoming infrastructural. I think the symposium was a good retort to that, but its clear that engagement cannot just be based on reception theory. We need to get our hands a little dirty.

As the symposium finished I was left wondering whether AI slop represents a temporary phenomenon existing only during a time when generative AI has a particular quality threshold, low enough to be recognised as poor or generic, yet good enough to produce something with a gimmick that is just enough to capture attention. The very concept of slop may be historically bounded, tied to a moment when AI generation quality occupies this uncanny valley of competence: capable enough to flood platforms with content that is just weird enough to grab interest, but incompetent enough to remain visibly artificial.

This state of affairs may not last – after all, why maintain a category for something that becomes everything?

Leave a comment