I’m not a hard-nosed computer scientist. I’m more interested in people than algorithms, and that’s why my research has taken me in the direction of hypertext, UX and narrative. That’s also why earlier this month I was so sad to hear about the death of Douglas Engelbart, the American Scientist who thought that computers could augment man’s intellect (excuse him the 1960’s gender language) and empower us as individuals and as a society. Engelbart gave the Mother of all Demos in 1968, and in one fell swoop introduced the world to graphical user interfaces, hypertext and the mouse. I was lucky enough to meet him at Hypertext 2005 in Santa Fe, and he was the very definition of a gentleman and a scholar.

It is also why I was proud to win (along with my co-authors) the Douglas Engelbart prize for best paper at ACM Hypertext 2013, for our work on location-based narrative. As it turns out, the last such award to be given in Doug’s lifetime.

Our work can’t compare with what he achieved, but I hope that he would like what we were trying to do.

There is a long tradition of hypertext applied to real world spaces, whether it be automatic tour guides or immersive fiction, and in the last three years there has been an explosion of location-based information systems for smart phones that link Wikipedia articles to the spaces around you, or let you leave virtual notes and annotations tied to a physical space. But despite this huge interest there was no way to really understand these systems as classical hypertexts.

In our paper we suggest that this is because in traditional navigational (node-link) hypertext the link carries two functions, it moves you conceptually from one place in a narrative to another, and it also moves you physically from one node to another. In a real world space you have no control over the physical movement – you can’t force people to walk from one spot to another – so the node-link model is a poor description of what is going on. Instead we suggested that you could model location-based information systems as sculptural hypertexts.

Sculptural hypertext is a name coined by Mark Bernstein, and demonstrated in both his 2001 paper on Card Shark, and also a 2001 paper that we wrote about our work at Chawton House. In sculptural hypertext all nodes can be considered as connected, and so rather than explicitly draw links between them (as in node-link models) you carve the links away. In effect a sculptural hypertext is a big state machine. Your state is compared to all the nodes in the system, and those that match are visible and can be selected as a next step. When you select a new node it changes your state in some way, and as a result alters the next nodes that you can see.

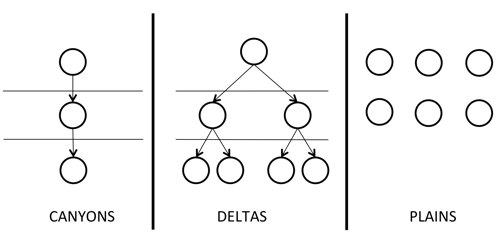

In our new paper we point out that there are three basic models of location-based systems: Canyons – a sequence of nodes/locations that must be visited in turn, Deltas – a tree of nodes/locations, where each user choice moves you down the tree and offers up new choices, and Plains – a set of nodes/locations that can be explored in any order. We then show that a simple model of sculptural hypertext can not only represent all three models, but mix them up into hybrid structures (such as a canyon that opens out into a plain).

The reason that I hope Doug Engelbart would appreciate our work is that were very conscious that a raw state machine model would not help people to create experiences or write stories for such a system. Instead we looked for higher level constructs that could be expressed in the state machine, and which would inspire authors and guide them in creating novel stories (this is similar to the work on poetics that we presented at ACM Hypertext last year).

For example, we allowed nodes to be Pinned (attached to a location) or UnPinned (available regardless of location), identified Chapters as an important construct that would help authors structure and manage their work, Timers that could automatically trigger chapter transitions (potentially allowing someone to explore a living play that unfolds around them), Stacks that provided a simple way of dealing with sequences, and Semantic Locations that would automatically map to points around you (so you tie a node to a query such as ‘nearest public place’ rather than a specific lat/long co-ordinate, meaning that you could pick up a story written for London, and play it in New York with locations appropriately substituted).

Our work on location-based narrative is still in an early stage, we have a simple implementation called GeoYarn, but we still have to investigate different reading models, and work with authors to explore what other high level patterns or structures might be useful to them.

It is impractical to imagine that a single model can achieve everything, and there are still things that some location-based apps do that do not fit into the model (for example, the idea of collecting items into an inventory; or interactions that occur within a single node). But we believe that the sculptural model could act as a framework for such things, in the same way that the node-link framework of the web has become a platform for a whole ecosystem of rich applications.

Doug Engelbart was all about building better tools, he reasoned that if you made better tools you didn’t just help solve one problem, but accelerated the solution of thousands. Our hope is that by having a common understanding of how location systems work we can move towards some kind of standardisation to allow authors to write location-based hypertexts that are independent of one particular app or reading tool. More importantly we can encourage more experimentation with hybrid forms (and thus explore more sophisticated storytelling).

I am very proud to have received an award associated with Doug Engelbart. He continues to be a genuine inspiration.

Leave a comment